Review: Sketching User Experiences

I found Sketching User Experiences to be an intelligent, far-reaching book that expanded my horizons but also left me somewhat frustrated.

As did many cities, London chose Bill Buxton’s Sketching User Experiences as the subject of the inaugural UX Book Club. I kicked off the discussion with my take on the book, and have hence decided to transform my notes into a written review for the benefit of anyone not present.

I found Sketching User Experiences to be an intelligent, far-reaching book that expanded my horizons but also left me somewhat frustrated. Buxton uses an inverted pyramid style, beginning broad and narrowing as he goes. This splits the book into what I felt were three sections (although Buxton himself declares only two parts: Design as Dreamcatcher andStories of Methods and Madness).

The first section, an analysis of the role of design, innovation and its business ecosystem, is to my mind the strongest. The ubiquitous iPod example surfaces early, but Buxton finds a way to inject this familiar narrative with fresh interest, by focusing on design strategy, acquisitions versus innovation, and the fundamental need for companies to create new stuff (faintly reminiscent of Marty Neumaier’s Zag). Buxton also elegantly dispels the myth that we cannot predict the future, demonstrating by historical example that supposedly new technologies typically have a minimum twenty year adoption curve.

The book then narrows to a discussion of process, asserting that “sketching is the one common action of designers”. I initially struggled with this definition, feeling it focused too much on visual output rather than our cognitive process. However, it soon becomes clear that Buxton isn’t interested so much in the sketch as artefact, but in sketching as an activity and a gerund. This culminates in his strongest chapter Clarity is not always the path to enlightenment which describes how sketching acts as a social object; the product of thought but also the catalyst for fresh ideas.

Sadly, from here, the book’s relevance declines. Examples and methods illustrated towards the end, while interesting, are clearly academic in their origin. As such, they may be fine for an M.A. project but, despite protestations of low overheads, they aren’t suitable for the fixed budgets and quick turnaround of agency user experience design. The latter sections are therefore at their best when they focus on simpler techniques. Chapters on tracing and photographs to as aids to sketching, and a convincing chapter on storytelling stand out.

I also remain unconvinced by the book’s overall stance. Buxton is a wonderfully knowledgeable author but his strong opinions often make Sketching User Experiences a paean to what I see as elitist practice. Big design up-front is regularly reinforced as the only worthwhile approach:

“Jumping in and immediately starting to build the product… is almost guaranteed to produce a mediocre product in which there is little innovation or market differentiation” (p141)

As a known Agile sympathiser, I have had Sketching User Experiences used as a weapon against me (“that’s not how Buxton says we do it”) and I found this narrow view hard to reconcile with my personal design ideology.

There are also small doses of intellectual arrogance that diminish the book’s impact. At the end of an unrealistic chapter on physical prototyping, Buxton asserts that any qualified interaction designer should be able to replicate this example in under thirty minutes. It’s a claim that begs the question of whether Buxton, or indeed anyone, has earned the right to impose their view of interaction design upon our community. The net result is that, although the book certainly helps designers, I’m not sure it helps the cause of design.

These ideological quibbles aside, I do recommend Sketching User Experiences. It was a strong choice for a book club and provided some good discussion points. It has also motivated me to draw more, to buy new Moleskines, improve the visibility of my sketching and sketches, focus on stories as important design tools, and to watch The Wizard Of Oz (you’ll see).

The making of Tourdust

A few weeks ago, a new travel startup called Tourdust quietly slipped into public release. It was my first major project for Clearleft, so I’d like to explain a little about the design process, challenges and decisions involved in its development.

A few weeks ago, a new travel startup called Tourdust quietly slipped into public release. It was my first major project for Clearleft, so I’d like to explain a little about the design process, challenges and decisions involved in its development.

Information architecture

The Tourdust proposition is a classic exploration of the long tail: linking offbeat, authentic tour experiences with travel geeks across the world. Think olive oil tours or bear watching, not package deals; a shared platform for small operations that may not even have websites of their own.

Since the site intends to house thousands of travel experiences, IA was a primary concern from the outset.Holidays involve a broad information space, with extensive metadata: duration, location, activity, organiser, price, availability, cost, and so on. Slicing through this data could be a daunting challenge for users, so an early task was to focus on how people understand and find travel experiences.

After design research, personas, scenarios and considerable thought, we concluded that the two critical factors in choosing an ‘active’ holiday (as opposed to a week sunbathing) werewhat the activity is and where it happens. It’s therefore no accident that these two variables are featured prominently on the site, as both navigation and headings. For a while, I even pressed (gently) for the site to be called everythingineverywhere.com.

Navigation

Since what and where operate independently of each other, they lend themselves well to faceted navigation. However, many faceted systems aren’t good at conveying their function, so we made the decision to split these two key variables off and turn them into primary navigation by means of dual nav bars, part breadcrumb and part hierarchical menu.

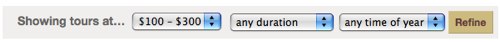

The other metadata is mostly taken care of by a “refine bar”. I believe it’s far better to show many results (particularly so in the early days when product numbers are low) and allow the user to trim the scope, than to create a bulky and elaborate “advanced search” feature that could confuse and easily return no results.

Unusual controls like these can be a risk; they’ll only be successful if users understand what they do, and how. The designer has to quickly suggest and demonstrate their operation through affordance and example. The affordance is largely visual: arrows, 3d overlap, and the behaviour of the menus as new options are selected. Demonstration by example occurs when a product is selected, possibly off the homepage. The dual nav is updated to show the intersection of activity and location (eg. “Cycling in Germany”), quickly establishing an understanding of how the controls work independently.

Of course, since these were uncommon controls, the proof was in the user testing. Paper prototypes were the order of the day here, mostly for budgetary reasons. Had more time been available we would have undoubtedly created HTML prototypes using Polypage to be watertight in our conclusions. However, they tested well for an unusual UI element and we felt confident this approach would allow for simple yet powerful navigation through this complex array of products.

Visual language

Another factor we agreed early on is that visual impact plays a huge role in the travel industry (not a massive leap of imagination, given the glossy large photographs seen in printed brochures). It was therefore very important for us to make the products as visually exciting as possible.

My early sketches involved very large, widescreen photos, and this detail was carried all the way into the final product. The widescreen format allows for some great detail of landscapes and panoramas, without the vertical overhead.

It also involves some tricky cropping mechanics. Most cameras take pictures with a 4×3 ratio (landscape) or 3×4 (portrait). The site halves the short side and instead uses an 8×3 ratio. Therefore, when a user—in this case, a tour operator—uploads an image, the system prompts them to crop the photo to show the top, middle or bottom half (the Maths is more complex for portrait shots). This cropping is initially done by clever CSS, repositioning the image vertically behind the 8×3 slot. Once a choice is made, the crop is made server-side for improved performance.

Process

We designed and built Tourdust as an Agile project, in collaboration with our Rails dev partners, New Bamboo. I’ve discussed the challenges of Agile design on A List Apart, but I believe that despite a few teething problems mid-project (mostly a cause of us not allowing enough lead time for design), the site is better than we could have created under waterfall methods.

In particular, since the clients were still exploring the business space whilst the site was being built, the business model changed halfway through development. With waterfall, this would have been beyond the point of no return, but with Agile’s flexibility we were able to accommodate the new requirements with only modest difficulty.

We also found ourselves fulfilling a strategic role as well as just designing the site experience. Frequently this involved reaching into the realms of service design, advising on features, functionality and proposition. One of the outcomes of this liaison was that great swathes of functionality were cut en route. “Worry about it when you need to worry about it” became a useful answer for many scalability questions. I think taking these bold decisions gives Tourdust more focus and a better user experience.

Endgame

Lest I paint too glowing a picture, the site isn’t perfect. Had we had more time, there are dozens of tweaks we’d have made. Imperfection is usually a tricky proposition for designers, particularly so at Clearleft: we do believe the devil is in the details, and our work is usually subjected to high scrutiny. Despite this, we’re proud of what was achieved on a modest budget, and hope we’ve given Anna and Ben the best platform to make Tourdust a success.

Of course, it’s a potentially difficult time to launch a startup. The recession is likely to dent the high-end, luxury travel market, meaning the site’s primary focus is currently on local, UK-based tours. But I do think, if the range is broad enough to gain traction, Tourdust can emerge on the other side in a strong position. I also couldn’t think of better people to take on this challenge than Anna and Ben. People who’ve put everything on the line to follow their dream are an inspiration, and it was a pleasure working with them. They’re true travel geeks and I think their confidence and love for the field will stand them in great stead.

Of course, it’s also down to the users, so I’d encourage you to have a play and I’d love to hear any comments you have about the site.

Why “best practice” must die

Anyone who’s worked in the web is aware of the “best practice” cult. To me, it’s a lazy creed that exhorts us to switch off and plunder others’ work, and the time has come to rebel.

Anyone who’s worked in the web is aware of the “best practice” cult. To me, it’s a lazy creed that exhorts us to switch off and plunder others’ work, and the time has come to rebel.

Firstly, there’s the pure language involved. “Best” implies something that cannot be improved upon. A world of best practice gives us creationism, chariots, and gramophones. It negates progress.

There’s also a more sinister side, which is when it’s wheeled out as an argument in design projects that are heading off the rails:

“Ah, but that’s not how eBay do it”.

The unspoken implication is that eBay know better than I, and therefore I should defer to their wisdom. It’s an argument that I find misguided more than insulting. “That’s not how eBay do it” is industrial, corporate thinking, entirely irrelevant to the 21st century. For the truth is that large companies often don’t have a clue about design. One’s skill and knowledge are entirely independent of the size of your employer: I’m confident I know as much about my profession as the employees at any large company.

The best practice trump card also fails because it doesn’t understand the nature of practical design. It’s not a transferable commodity: you can’t just screw a design solution into place. Good design must be appropriate and relevant to the particular problem. The factors involved—technological, strategic, sociological—are far too complex and variable for a plug and play approach. To say “Well, a dropdown worked here…” is to ignore factors that can actually work in your favour. A company that rejects the easy route and takes the time to understand technology, strategy and users can offer designs that makes it stand out from the rest.

I’m not advocating isolating oneself from the surrounding environment. For instance, at Clearleft, we regularly perform competitor analysis at the start of a project. It’s useful to see where others’ strengths and weaknesses lie, and helps us understand the landscape. However, not once has it given me the answer to a design problem. That always comes later, with thought, with detail, and after many failed attempts.

So let’s not allow the enforced limitation and unvoiced threats of “best practice” to pollute our thinking. It’s harder work, sure, but standing out and being better always is.

The h1 debate

Warning: There follows an arcane debate about HTML semantics, which will be extremely tedious to some.

Warning: There follows an arcane debate about HTML semantics, which will be extremely tedious to some.

Today has seen a minor revival of one the web’s perennial debates: whether the site header or page header is the most important. Its trivial intractability is perhaps only exceeded by the old UI chestnut of whether positive confirmation buttons should go on the left or right (think OK/Cancel versus Prev/Next). Frankly, it matters little, but I can’t sleep and I’m not one to miss out on a nuanced semantic debate.

Right now, you’re on my site Ineffable, reading a post The h1 debate. So which is the most important header on the page? Whichever is chosen should be marked up as <h1> (the HTML for the topmost header) for reasons of search engine optimisation, clean code, and so on.

The case for the site header

A purist might say that semantically and logically the site’s name is the primary tier. This would mean the hierarchy for this paragraph is: Ineffable > The h1 debate > The case for the site header.

While perhaps correct from an ontological perspective (a site has many articles, with many sub-sections), this has the drawback that the <h1> is the same for every page on the site. This is bad for search engines and may make orientation more different for those using screen readers. I also have a more fundamental concern, namely that this imposes a model that matches the designer’s understanding, but not the user’s.

The case for the page title

Pedantry is often important when it comes to good markup, but here I believe pragmatism must win out. This pragmatism arises when looking at the problem from the user’s perspective.

A user arriving at the site may indeed want to orientate themselves by seeing the name of the site, but their main goal is to find relevant information. This is particularly the case if they’ve come via a search engine, wherein they entered text of interest to them and leapt straight into the article itself.

The most important thing to a user is therefore what the page is about. This topic is far more likely to be represented by its title than the site name, and it’s logical that this title should be marked up as the <h1>.

My chosen hierarchy for this section is therefore The h1 debate > The case for the page title, with Ineffable possibly coming in as an <h3>. Note that, while an <h3> may be a subsection of <h2>, this isn’t demanded by the spec; and I think this is the right solution for this particular site.

This said, the answer may be that design classic “it depends” – with contributory factors including the size of the site, its purpose, and user behaviour. Particularly for small sites where users frequently navigate from the homepage down, I could see a site name <h1> being appropriate, while large sites with lots of ‘deep link’ traffic would be better suited by a page title <h1>.

Coping with a mainstream Twitter

The practical upshot is plenty of new users, including several of my real-life friends. While it’s great to have them on Twitter, I have my own selfish concern: will I be able to cope?

January was the month that Twitter lurched towards the British mainstream. Stats show an astronomical rise in site and search traffic, and the rich and famous are now falling over themselves to connect with their fawning public.

One may ask why this tipping point has happened first in the UK, rather than the States or elsewhere. One possible explanation is that a small number of influential celebrity types have hastened this outcome, and it’d be easy to fall into a daft sociocultural analysis of Britain the country and Britain the network. Stephen Fry as the powerful Gladwellian connector, uniting the geeks and the unwashed, previously so suspicious of each other!

My money’s on random chance. The initial conditions were set, after which chaos theory is the dominant force (yes, perhaps I have been listening to Jeremy too much).

The practical upshot is plenty of new users, including several of my real-life friends. They’re perhaps still on the early adopter side of mainstream but they’re not the type to, for instance, write blog posts about why people are joining Twitter. While it’s great to have them on Twitter, I have my own selfish concern: will I be able to cope?

I’ve previously mentioned that I have an approximate following threshold of 250. My workload and lifestyle enforce that personal limit, and I can’t realistically keep up to date with more people. So if my less geeky friends continue to join, whom do I drop? The model’s different from Facebook, where I can simply accumulate “friends” (a virtual notch on the bedpost) and then largely ignore them. So do I drop existing Twitterers, many whom I’ve never met but still give me a wealth of inspiration and knowledge, or friends whom I miss and am always eager to hear from? Ambient intimacy or friendship?

It’s a quandary. I’ve been trying to convince friends to join Twitter for a long time and it would be an irony if, once they join, I admit I don’t want to follow them. Yet I’m already operating a one-in-one-out policy, and something will have to give. My likely approach will be to take a much more relaxed and liberal approach to unfollowing people. Just as I’ll go and talk to various people at a party, so my attention will shift around a bit online. It’s either that or I face a cacophony in which I can hear no one.

However, I’m aware that people have very different attitudes to being unfollowed, so I’ll treat this post as a prophylactic excuse. Seriously, it’s not you, it’s me.